Look, SQL joins aren't that scary.

I've sat through dozens of technical interviews—both as the nervous guy in the hot seat and the cynical guy holding the clipboard. Most candidates blow it on SQL joins because they try to memorize definitions from a 2012 blog post instead of understanding how data actually moves. It's frustrating. If you can't explain a join, you can't work with relational databases. Period.

Basically, a join is just a way to stitch two tables together based on a common thread. That's it. You've got an 'Orders' table and a 'Customers' table. You want to see who bought what? You join them. Simple. But the way you stitch them matters because it determines what happens to the data that doesn't have a match. That's where people trip up.

The Inner Join: The 'Only If You're Both Invited' Rule

This is your bread and butter. I'd say 90% of the queries I've written in 15 years are inner joins. An Inner Join only returns rows where there's a match in both tables. If a customer hasn't placed an order, they don't show up. If an order (somehow) doesn't have a valid customer ID, it's gone.

Think of it like a high-school dance. Only the couples who both showed up get on the floor. The wallflowers? Ignored. Data that doesn't have a partner in the other table gets tossed out of the result set. It's clean. It's precise. It's usually what the boss wants when they ask for 'a list of active users.'

The Left Join: My Personal Favorite

Honestly? I use Left Joins more than I probably should. A Left Join (or Left Outer Join) keeps everything from the first table (the 'left' one) and only brings in matching stuff from the second table. If there's no match? You get a NULL.

Why is this useful? Because sometimes you need to find the gaps. I had a client once who wanted to know which products weren't selling. An Inner Join would've hidden those products. A Left Join showed every single product, and for the ones with no sales, the 'SalesAmount' column was just a big fat NULL. That's the real kicker—knowing what's missing is often more valuable than knowing what's there.

- Pro tip: In an interview, if they ask how to find 'records in A that aren't in B,' the answer is a Left Join where the B.id is NULL.

Right Joins and Why I Barely Use Them

Okay, here's a hot take: Right Joins are mostly useless. A Right Join is just a Left Join with the tables swapped. It keeps everything from the right table and matches from the left. In over a decade of freelancing, I've rarely seen a situation where a Right Join was 'better' than just reordering your query to use a Left Join. It makes the code harder to read. Most devs read from left to right, so keep your primary table on the left. Just my two cents.

The Full Join: The 'Bring Everybody' Approach

The Full Outer Join is the messy one. It returns everything from both tables. If there's a match, it lines them up. If not, it fills the gaps with NULLs on either side. It's like a family reunion where everyone is invited, even the third cousins nobody likes. You don't see these often in standard web apps, but in big data warehousing or messy migrations, they're a lifesaver for auditing data integrity.

Wait, What About Cross Joins?

I've seen junior devs accidentally trigger a Cross Join and crash a production server. Not fun. A Cross Join creates a Cartesian product. It pairs every single row from table A with every single row from table B. If you have 100 rows in each, you get 10,000 rows back. Use this when you need every possible combination of something—like colors and sizes for a clothing inventory—but otherwise, stay away. It's a resource hog.

How to Talk About This in an Interview

Don't just recite syntax. Interviewers hate that. Instead, talk about the logic. Here's a quick cheat sheet for when you're under the lights:

- Inner: The intersection. Match only.

- Left: Everything on the left, NULLs for the rest. Great for finding 'missing' data.

- Right: Like Left, but backwards. (Mention you prefer Left for readability).

- Full: The whole kitchen sink. Everything from both sides.

- Self Join: When a table joins itself (like an 'Employees' table where a 'ManagerID' points back to another 'EmployeeID'). This is a classic 'gotcha' question.

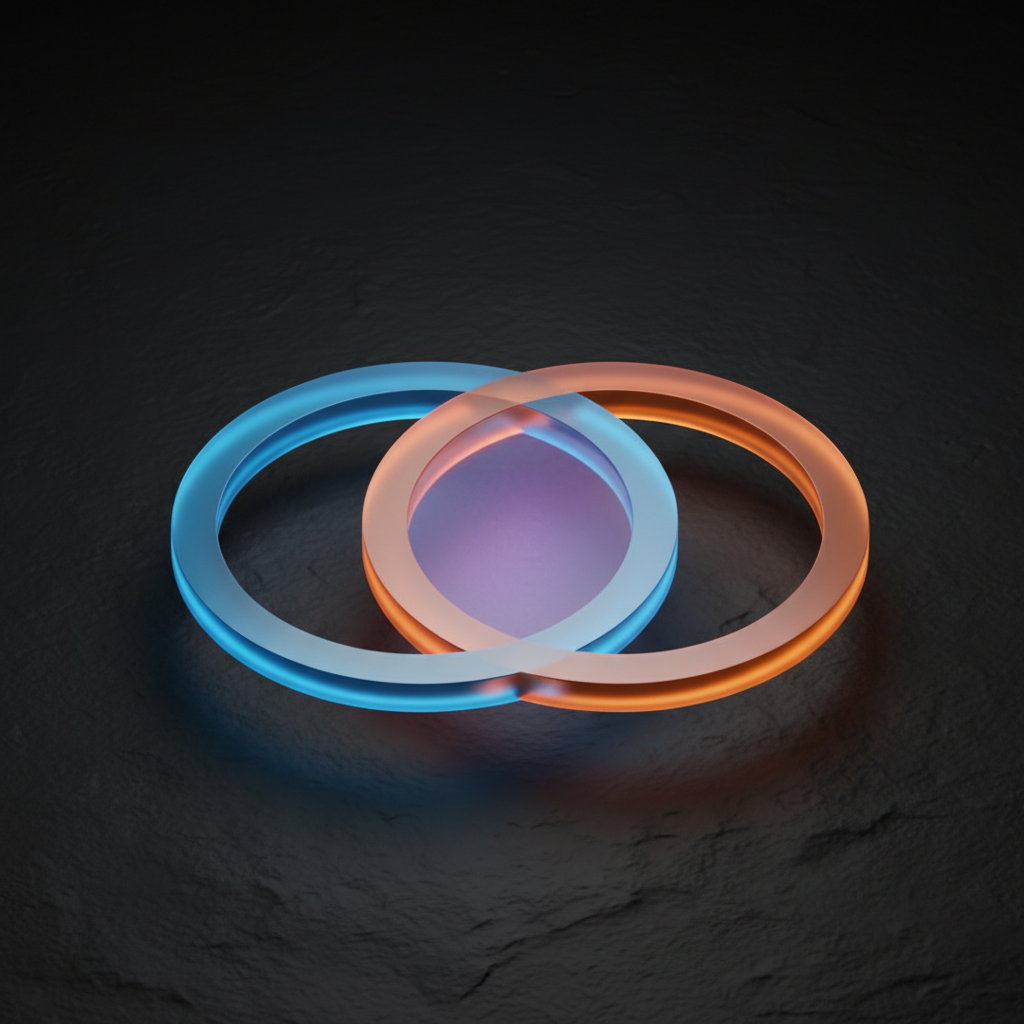

Look, the real secret to SQL is that it's all about sets. If you can visualize the circles of a Venn diagram, you've already won half the battle. Just don't forget your 'ON' clause, or you'll end up with a mess that no amount of coffee can fix. I've been there. It's not pretty.

Comments

Be the first to comment.